Wells Fargo: The High Cost of Culture Crisis

- September 15, 2021

- 6:06 pm

- Theresa Agresta

What went wrong at Wells Fargo is well documented. But why it went wrong is a lesson we can all learn from. Because at Wells Fargo, a seemingly successful “sales culture” was brewing toxic side effects to the tune a $185 million fine and upwards of $8 billion in revenue loss.

How could this happen to such a well-established financial institution with a culture rooted in strength and trust? Why did Wells Fargo’s employees feel they had the liberty to fabricate millions of unauthorized accounts?

Unethical employees were not the cause. They were the effect.

In a Fortune magazine interview, the new Wells Fargo CEO, Tim Sloan, said the company is committed to fixing and remediating everything that is broken and creating a better company culture.

But, to intentionally shape a new culture, it’s critical to understand the current culture and the “unwritten rules of engagement” that created it. And, it’s not that simple. Because, as is often the case, the company’s worst behaviors originated from the same patterns responsible for its overwhelming success.

Why did it go wrong? The answer is in the Archetypes.

Wells Fargo’s culture has not been measured by our organizational survey tool, but in the transparency that’s occurred after the scandal, we see evidence of the Hero, Ruler, and Revolutionary patterns. With every strength these Archetypes bring to the table, unintended shadow sides also show up.

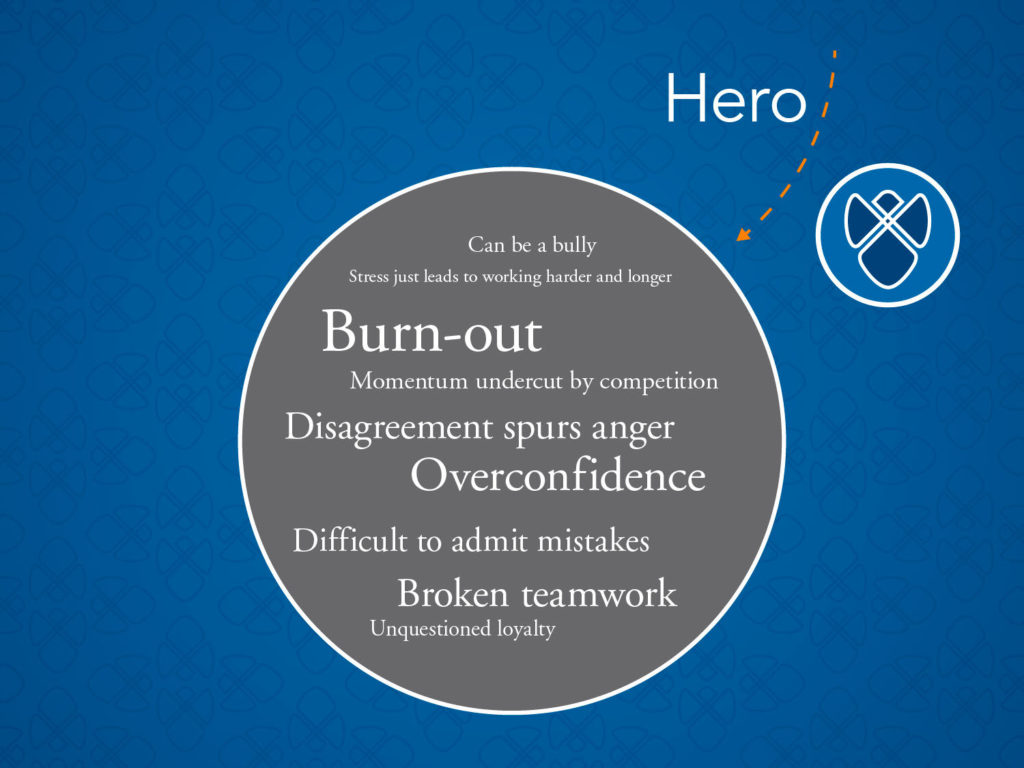

The Hero Archetype at Wells Fargo

At the root of Wells Fargo’s scandal and culture crisis is one prominent segment of the company’s business – the retail banking unit. In this area, we see heavy evidence of the Hero Archetype.

- A hard-charging sales culture and obsession with cross-selling created a drive to win at all costs.

- The internal call-to-action was “Go for Gr-eight”, a campaign that motivated employees to sell 8 products to every customer.

The Hero Archetype worked for them. While the average bank only sold 2.6 products to every customer, Wells Fargo was charging ahead with an unheard-of average of 6.1. This competitive drive transformed the company from the country’s #9 bank in the late ‘90s, operating largely in California, to the top-performing bank in the country by 2015. In many ways, Wells Fargo was the envy of the industry.

But, the shadow side of the Hero Archetype was also at play. Here, we see warning signs of a pending culture implosion.

- Sales results at Wells Fargo weren’t reported every month as they are in many organizations. Instead, they were demanded in some cases as often as every hour.

- Sales winners were publically celebrated. Low performers were subject to humiliation, demotion, and even firing. No excuses were tolerated if you didn’t meet your quota.

- Employee burnout and turnover were high – 41% in one year.

- In a lawsuit, a former employee said, “Managers constantly hound, berate, demean and threaten employees to meet these unreachable quotas.”

But there was more at play. They were also acting as a Revolutionary.

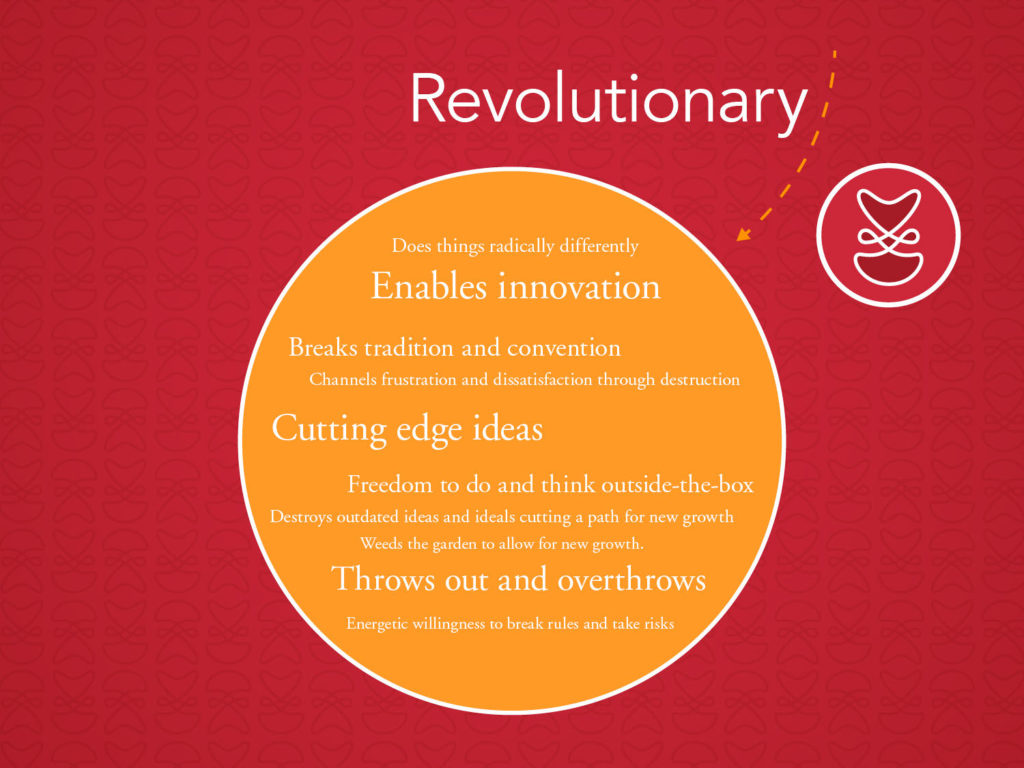

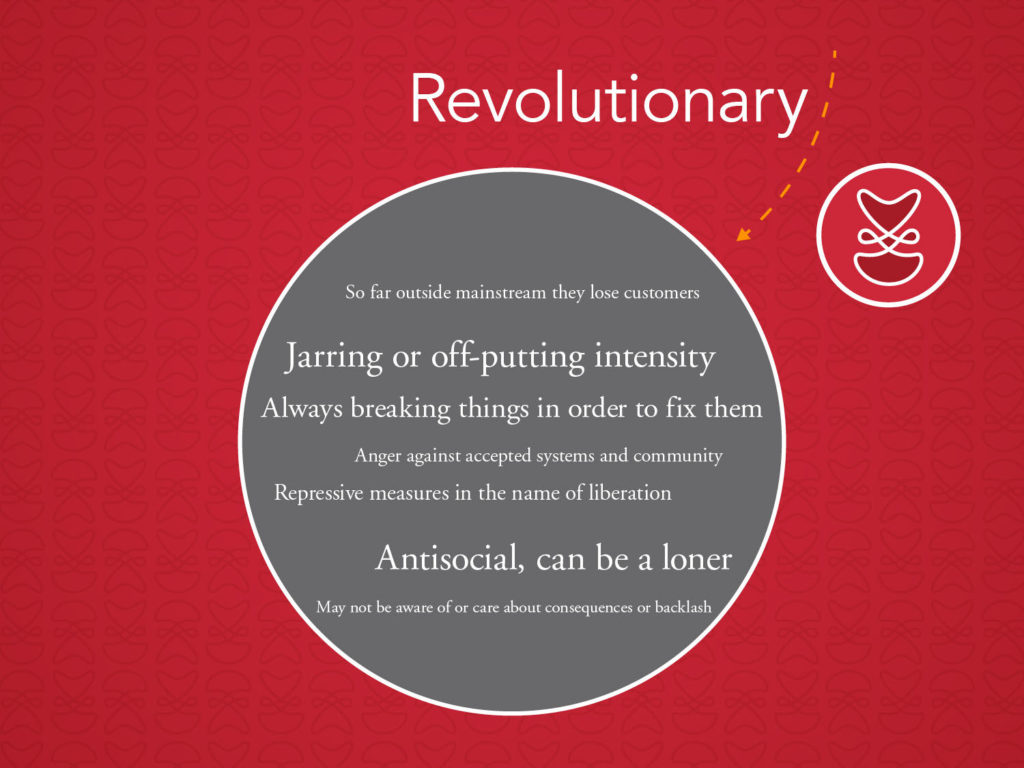

The Revolutionary Archetype at Wells Fargo

There is significant evidence of the Revolutionary Archetype in the culture that led to Wells Fargo’s scandal.

- The banking unit was breaking the industry mold. Even the language they used created new rules.

- They sold products instead of servicing customers.

- They worked at ‘stores’ instead of branches.

The evidence is compounded by the Revolutionary’s shadow side.

- While what the employees did – opening accounts and issuing products that customers didn’t ask for – was and is, against the “written rules” at Wells Fargo, the Revolutionary Archetype’s shadow side makes it acceptable to look the other way and shrug off official guidelines.

- Rule breakers were actually rewarded

- Remember that 41% employee turnover? That is almost expected in a retail environment. What would ordinarily be cause for concern at other financial institutions, where stability and consistency are key to success, went unaddressed.

- One of the key consequences of the Revolutionary shadow is a lack of awareness of what you are leaving in your wake.

So why did this go unnoticed higher up in the corporation where top leaders under-reacted for years? This is where the Ruler Archetype shows up.

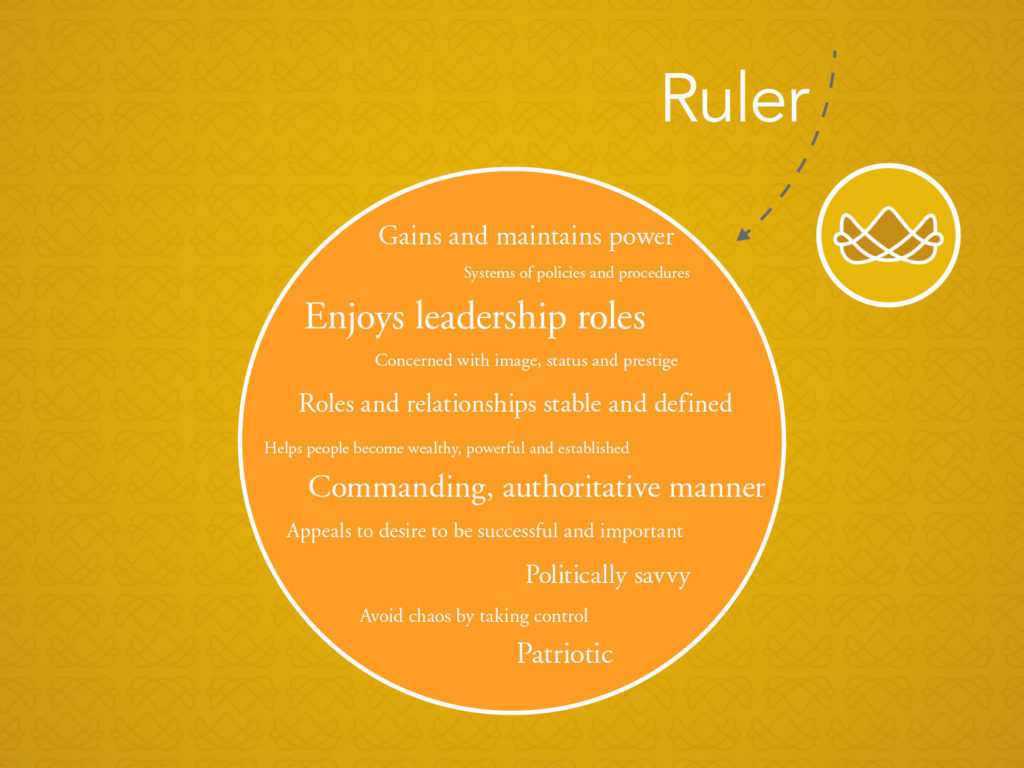

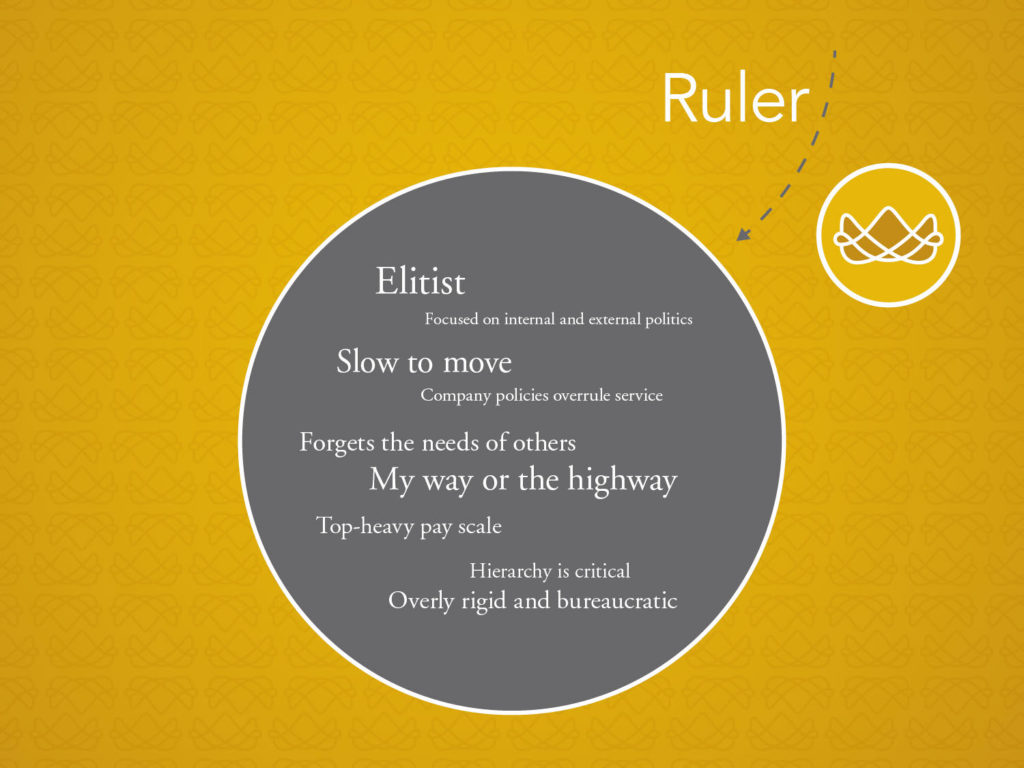

The Ruler Archetype at Wells Fargo

At Wells Fargo, there are many positive aspects to this Ruler that work on many levels – recall, they did rise to the #1 position in their market.

- The Ruler is also seen in the company’s strong deference to the leaders of each siloed business unit. Told to “run it like you own it”, they each had the power to rule their own fiefdom within the bank.

However, in this crisis, the shadow side of the Ruler created a critical a shortcoming through a culture that is top-heavy and slow to move.

- It’s been revealed that the leaders of the retail banking unit did not like to be challenged or to hear negative information. People were discouraged from airing contrary views (because in a Ruler culture, you definitely don’t tell the emperor he has no clothes).

- Outside the retail banking unit, a sprawling corporate bureaucracy compounded the problem leaving no clear lines of responsibility.

Could the culture crisis have been avoided?

In hindsight, it’s easy to see how the culture at Wells Fargo went awry. And, how the very things that make an organization strong can brew glaring problems when you cross from a strength to a shadow side of an Archetypal pattern.

We can’t help but wonder if the leaders at Wells Fargo had Archetypal insight on their culture in advance…would things have turned out differently? With awareness, could they have proactively faced their own shadows?

The lesson for all of us.

While Wells Fargo presents a monumental example, the storyline can be similar in companies of any size. Is your company experiencing negative side effects of your Archetypal shadows? Like Wells Fargo, are you excelling, but at the same time burning out your team? Are you breaking the mold…at the cost of ethics? Are you so stuck in a process that you’re unprepared to shift quickly in a crisis?